Charles Vorkas - Musings from Lilongwe, Malawi

by Charles Vorkas

Charles (MD'11) is a Fogarty Scholar working with the University of North Carolina in Lilongwe, Malawi

Dr. Dumbani Kayira and Charles Kyriakos Vorkas standing in front of the Bwaila In-patient TB Ward where they study HIV/TB and multi-drug resistant tuberculosis.

Dr. Dumbani Kayira and Charles Kyriakos Vorkas standing in front of the Bwaila In-patient TB Ward where they study HIV/TB and multi-drug resistant tuberculosis.

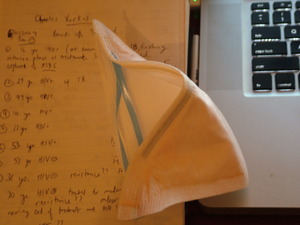

September 4, 2009UNC Guest House I just completed my first month in Lilongwe and a detailed communication is long overdue. I am well and settling into a rhythm. The skill set I need to be happy here are different than what I am used to. While I am in the capital city, Lilongwe is more like a big town and I often feel like this is the suburban experience I never had. While you can walk to the produce market, it takes about 40 minutes. Since everything is spread apart, a car is a necessity. As many of you already know, most of the world uses manual transmission (stick shift). I have had a lot more fun driving stick. I actually feel like I have full control of the vehicle. Of course, driving here is more challenging because of the narrow roads and numerous obstacles. Lots of bikes and pedestrians in the street as there are few sidewalks. When you get out of the city, there are goat and cow crossings. But, don’t worry Mom, I am driving slowly and safely! As for my daily routine: I am splitting my week between research and clinical work. I spend some mornings in the Kamuzu Central Hospital, which is Lilongwe’s largest clinical center. There are several departments, including an operating theater and a surgical intensive care unit. The care here is not particularly good and, as a medical student with minimal experience treating disease, it is a very frustrating and humbling experience. Most of the time, I feel helpless. But then again, I am more trained than many of the Malawian “interns” who have completed medical school, but have no hands-on experience. Most of the patients on the medicine ward are HIV positive and many have progressed to stage 3 and 4 AIDS. There is no isolation of airborne infection risks, so all the suspected TB patients are placed in a long well-ventilated corridor. I brought a bunch of N-95 masks (thank you, New York Hospital), but it is just not practical to wear them as you are potentially exposed all the time.  Tools of the trade: N-95 mask, notebook, and computer.The one time I did wear a mask was when we went on a home visit to a suspected multi-drug resistant tuberculosis patient’s home. This 22-year-old, HIV negative woman was diagnosed with tuberculosis in December of last year and went on first-line treatment: Rifampicin, Isoniazid, Ethambutol and Pyrazinamide combined in one pill for two months and then rifampicin and isoniazid combined in one pill for three months. During this therapy, the patient is supposed to submit sputum samples regularly to determine if therapy is effective. This patient completed 5 months of therapy, but continued to produce sputum positive for tuberculosis. She was then treated empirically for drug-resistant tuberculosis as the district health department did not have the capacity to perform anti-TB drug resistance assays. The patient continues to deteriorate on second-line therapy and there is fear that she may be resistant to second-line drugs as well. The patient’s mother recently submitted sputum samples which are also positive for tuberculosis, so we think that she too may have the same resistant strains as her daughter. Don’t worry Mom, at least I was wearing my mask when I saw them. Tuberculosis exposure usually results in latent infection, but in the malnourished or immunocompromised, it can result in active disease. My project focuses on characterizing the patients on the TB wards in Bwaila Hospital, a district clinical center with even fewer resources than Kamuzu Central. The TB ward is a scary place. Patients are sprawled out on old, rusty beds, one next to the other. They are all TB treatment failures, meaning that this is at least the second time they are receiving TB treatment. Many of them likely have drug-resistant disease, but since the Malawian Ministry of Health has yet to effectively implement drug-resistance testing, some patients are not receiving the second-line therapy they need.

Tools of the trade: N-95 mask, notebook, and computer.The one time I did wear a mask was when we went on a home visit to a suspected multi-drug resistant tuberculosis patient’s home. This 22-year-old, HIV negative woman was diagnosed with tuberculosis in December of last year and went on first-line treatment: Rifampicin, Isoniazid, Ethambutol and Pyrazinamide combined in one pill for two months and then rifampicin and isoniazid combined in one pill for three months. During this therapy, the patient is supposed to submit sputum samples regularly to determine if therapy is effective. This patient completed 5 months of therapy, but continued to produce sputum positive for tuberculosis. She was then treated empirically for drug-resistant tuberculosis as the district health department did not have the capacity to perform anti-TB drug resistance assays. The patient continues to deteriorate on second-line therapy and there is fear that she may be resistant to second-line drugs as well. The patient’s mother recently submitted sputum samples which are also positive for tuberculosis, so we think that she too may have the same resistant strains as her daughter. Don’t worry Mom, at least I was wearing my mask when I saw them. Tuberculosis exposure usually results in latent infection, but in the malnourished or immunocompromised, it can result in active disease. My project focuses on characterizing the patients on the TB wards in Bwaila Hospital, a district clinical center with even fewer resources than Kamuzu Central. The TB ward is a scary place. Patients are sprawled out on old, rusty beds, one next to the other. They are all TB treatment failures, meaning that this is at least the second time they are receiving TB treatment. Many of them likely have drug-resistant disease, but since the Malawian Ministry of Health has yet to effectively implement drug-resistance testing, some patients are not receiving the second-line therapy they need.  Charles Kyriakos Vorkas reading Chest X-rays pre and post intensive phase of treatment.I will focus on analyzing sputum cultures for response to medications and drug-resistance, with the intent to properly treat tuberculosis and prevent further emergence of resistance. This is relatively easy to do in a controlled setting, like a tuberculosis ward. But real problems lie in the community where the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended direct-observation of therapy-short term (DOTS) is often not implemented. In Malawi, patients—adults and children alike–are accompanied by guardians who are responsible for feeding and caring for the patient during their hospital stay. The guardian is also expected to accompany the patient for outpatient visits, which include visits to the Martin Preuss Center, the National Tuberculosis Registry of Malawi. I question to what extent we can trust these guardians in ensuring the TB patients take their medicines religiously. But this is the most practical use of resources. Drug-resistance can arise spontaneously, but selection pressures for resistance arise when people don’t take their medicines every day. This may be the problem with our suspected multi-drug resistant patient. Her mother claims that she takes her therapy regularly. There is also a team from the Martin Preuss center that visits daily to administer injectable second-line drugs and watch her take her oral medication. But perhaps this team does not watch her swallow her pills.

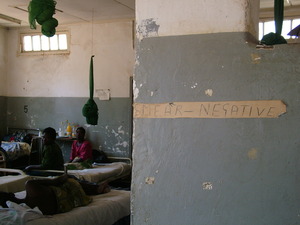

Charles Kyriakos Vorkas reading Chest X-rays pre and post intensive phase of treatment.I will focus on analyzing sputum cultures for response to medications and drug-resistance, with the intent to properly treat tuberculosis and prevent further emergence of resistance. This is relatively easy to do in a controlled setting, like a tuberculosis ward. But real problems lie in the community where the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended direct-observation of therapy-short term (DOTS) is often not implemented. In Malawi, patients—adults and children alike–are accompanied by guardians who are responsible for feeding and caring for the patient during their hospital stay. The guardian is also expected to accompany the patient for outpatient visits, which include visits to the Martin Preuss Center, the National Tuberculosis Registry of Malawi. I question to what extent we can trust these guardians in ensuring the TB patients take their medicines religiously. But this is the most practical use of resources. Drug-resistance can arise spontaneously, but selection pressures for resistance arise when people don’t take their medicines every day. This may be the problem with our suspected multi-drug resistant patient. Her mother claims that she takes her therapy regularly. There is also a team from the Martin Preuss center that visits daily to administer injectable second-line drugs and watch her take her oral medication. But perhaps this team does not watch her swallow her pills.  The male smear positive tuberculosis ward where retreatment patients with confirmed sputum+ TB would receive 2 months of inpatient therapy.We just completed running the HAIN assay on this young woman’s sputum. She is definitely isoniazid resistant, but the results of the rifampicin sensitivity were inconclusive. We suspect that she is also rifampicin resistant and at least multi-drug resistant. We will not know if she also has resistance to second-line drugs for a couple of weeks when her sputum cultures return. If she is in fact resistant to the second-line therapy on which she is currently deteriorating, she will be the first officially reported case of extremely drug-resistant tuberculosis in Malawi (XDR-TB)—an exciting, though unfortunate finding.

The male smear positive tuberculosis ward where retreatment patients with confirmed sputum+ TB would receive 2 months of inpatient therapy.We just completed running the HAIN assay on this young woman’s sputum. She is definitely isoniazid resistant, but the results of the rifampicin sensitivity were inconclusive. We suspect that she is also rifampicin resistant and at least multi-drug resistant. We will not know if she also has resistance to second-line drugs for a couple of weeks when her sputum cultures return. If she is in fact resistant to the second-line therapy on which she is currently deteriorating, she will be the first officially reported case of extremely drug-resistant tuberculosis in Malawi (XDR-TB)—an exciting, though unfortunate finding.

Excerpted, with permission, from Charles Vorkas' blog, "Musings from Lilongwe, Malawi"

Female smear negative ward where female retreatment patients with suspected TB by clinical picture would receive two months of inpatient treatment.

Female smear negative ward where female retreatment patients with suspected TB by clinical picture would receive two months of inpatient treatment.

A "natural" X-ray light box- an HIV/TB patient with miliary tuberculosis.

A "natural" X-ray light box- an HIV/TB patient with miliary tuberculosis.

Weill Cornell Medicine Center for Global Health

Center for Global Health

420 East 70th Street, 4th Floor, Suite LH-455

New York, NY 10021

Phone: (646) 962-8140

Fax: (646) 962-0285